Monetary policy mayhem, or how not to solve the ‘cost of living’ crisis (part 2 of 3)

There is a strong case for innovation in monetary policy practice – but the limits of central banking-led economic governance are clearly in sight

In part 1 of this post, I noted that UK economic policy-makers’ response to rising inflation – which is causing crippling increases in living costs for millions of people – is likely to make many households even poorer, without tackling the supply-side causes of high inflation.

At least part of the problem is that inflation itself is seen as the crisis, because of the impact it has on sterling’s role in a financialised growth model, rather than a cause of a wider cost of living crisis.

But the growth model is not working, and its salvaging should not be the be-all and end-all of economic policy. Policy-makers seem to lack both the tools and the will to prevent or alleviate deepening hardship. It is time to do things differently.

Reserve army

So far, the Bank of England has elected to tackle inflation by raising interest rates; a policy which may achieve its headline objective, but is also likely to cause recession and higher unemployment.

Frank van Lerven and Dominic Caddick of the New Economics Foundation (NEF) offer an alternative, or at least corrective, approach.

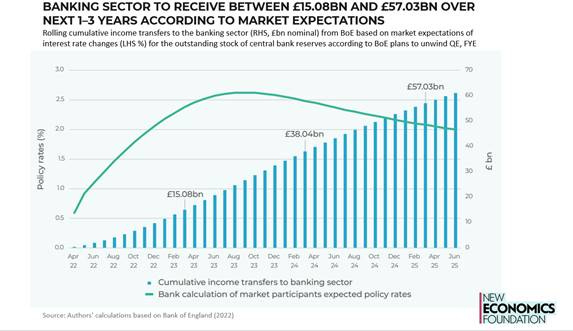

They start from the recognition that, if interest rates continue to rise as expected, the banking sector will receive an enormous windfall, given that the higher rate will be paid on reserves that commercial banks hold at the Bank of England.

As the chart shows, this transfer from central bank to private banks could amount to £57 billion over the next three years, significantly higher than funds the government has made available to support the most deprived households to address higher living costs.

The proposal is that the Bank not pay this interest, or at least not all of it (a tiered reserve system would mean interest was payable on only a portion of the reserves held at the Bank). This would be justified in terms of fairness: the banking sector is no more deserving of this windfall than anyone else (and perhaps rather less!), so it should be captured to provide support to those in greatest need.

Always

Part 1 explored the inconvenient fact that monetary policy has a limited role in addressing inflation (at least not without causing even bigger problems). But the NEF proposal is aided by the fact that it might help monetary policy to be more effective.

As the International Monetary Fund has also argued, a tiered reserve system would make borrowing more expensive, because it affects banks’ profitability, and higher costs would probably be passed on to borrowers. In other words, it would mean that raising interest rates actually does what it says on the tin, with the Bank rate passed on to borrowers, dampening inflation.

This pass-through impact might not fully materialise – it depends on how the tiering is designed – but hoisting central bankers with their own petard at least has a degree of comedy value.

On balance, I have no major objections to the NEF proposal (although others do, with some merit, as I discuss below). I am sceptical, however, of three things. First, since politics usually trumps economics, I doubt that UK central bankers are about to transform their supervisory approach towards commercial banks from collaborative to punitive. This is despite similar practices already being in place in the Eurozone and Japan (and despite the the advocacy of Adair Turner). Old habits die hard.

Some fear the ensuing upheaval would have adverse consequences for the finance sector: I am not really qualified to judge this prospect, but I suspect it would be a problem for the banks that, sensibly managed, would not be transmitted to the rest of the economy. Alas, while the Bank of England does not always privilege the City of London, it almost always does. As I argued in part 1, to make monetary policy models fit reality, the Bank expects workers, not bankers, to make sacrifices.

Second, it is not clear that we should want monetary policy to become more effective! My research with John Evemy and Ed Yates has demonstrated how very low interest rates (enabling cheap credit) contributed to the UK’s productivity slowdown. But this does not mean that we should jump at the chance of making credit more expensive through higher interest rates, without a wider set of economic reforms to prevent unemployment and further hardship.

Third, I do not believe that technocratic fixes to the rising cost of living are likely to be sufficient or durable (to be clear: van Lerven and Caddick do not claim that they would be). The rebalancing required, from supporting unearned profiteering to tackling unnecessary inequalities, must be fought for in the sunshine, with the weight of public opinion hopefully counteracting the force of path dependency.

Easing

It is worth considering the historical context in which central bank reserves have taken on greater significance. Previously used to facilitate inter-bank lending (IBL), the collapse in IBL amid the 2008 financial crisis required strategic central bank interventions.

Enter quantitative easing (QE). QE is a process by which the government buys its own debt. Technically, the Bank of England buys Treasury debt. But it does so by creating massive amounts of central bank reserves: new money credited to private banks. The banks then compensate the previous holders of government bonds.

In the process, the increase in central bank reserve volumes oversees the resumption of IBL (for all intents and purposes, it replaces conventional IBL), and more generally helps the banks to recapitalise, that is, avoid insolvency.

The original intention of QE was, ostensibly, for private investors to stimulate the economy by replacing investment in government debt with investment in riskier assets and productive activity. Unsurprisingly, this new twist on ‘trickle down’ economics was, at best, only partially successful.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, QE became focused primarily on financing government spending rather than economic stimulus – albeit still utilising the central bank reserve accounts of private banks. Since 2020, the Bank of England’s purchases of government bonds have tracked quite precisely the public sector’s borrowing requirement.

Ensuring that the government’s debt servicing costs remained low had always been a secondary objective of QE; this aim is now front-and-centre, although the Bank continues to deny it. The Bank of England can of course simply create money for the government to spend – and indeed has done so – but evidently prefers to act via private banks.

The question of whether QE was the ‘least bad option’ to support the economy after 2008, and underpin the public finances throughout the pandemic, remains arguable. What we know with more certainty – because the Bank admits it – is that QE has exacerbated inequality.

Contra monetarism, large-scale money creation by the public sector has not caused inflation, but in protecting the financial assets of the rich (while the poor have borne the brunt of spending cuts elsewhere in government) it has ultimately amplified the impact of inflation on the most deprived households.

Objections

Some commentators have argued that, if reserves were to attract no interest payments, banks’ clamour to dump their holdings would further increase inflation. But this is not the case: the Bank would simply need to make reserve holdings mandatory.

The more serious objection is that, because holding central banks reserves would be mandatory, not paying interest (even on a portion of the reserves) makes it a form of taxation on private banks. Let us be clear: the banks are always going to have reserve accounts, because it is in their interest to do so. But obliging them to do so would, so the story goes, render the banking sector the victim of oppression by a tyrannical government (or something like that).

Similarly, other critics have pointed out that a tiered reserve system cannot be employed because QE has bloated reserve holdings. But this is not the gotcha they seem to think it is: the system is justifiable precisely because of QE-related bloating.

We must not mistake features for bugs. As Toby Nangle and Tony Yates identify in the Financial Times, ‘[i]ncreasing the stock of QE would push taxes on commercial banks higher; unwinding QE would cut taxes on commercial banks’. Nangle and Yates write with mild concern about this dynamic. But it is literally what the proposed system is for, that is, redistributing the unearned windfall private banks have gained from QE.

No QE money, no problems. The system’s specific settings could of course be modified as and when the Bank moves towards its goal of unwinding QE (a decades-long agenda).

That said, it probably should be recognised that a tiered reserve system is as much a fiscal policy as a monetary policy (just like QE in general, although the big lie persists). Nangle and Yates are onto something when they conclude:

If the Chancellor wanted to tax the banks more, why not… er… tax the banks?

Of course, the notion that monetary policy is set independently of the Treasury’s wider macroeconomic policy agenda has long since been debunked – it was always more a confidence trick than anything else.

Yet the essential point here is that the limits of monetary policy activism are clearly now in sight. I think the NEF plan is worth a go. And I am fairly sure in fact that the government will soon move in this direction – but only because it would be a way of avoiding the fiscal policy reckoning that the UK really needs.

(£57 billion generated by monetary policy manoeuvrings could fund some of Rishi Sunak’s tax cuts without the need for further public spending reductions.)

But it will not on its own come close to tackling the cost of living crisis. For that, the wider reckoning will be required. The third and final part of this post will be my attempt to conjure up some solutions in this regard.