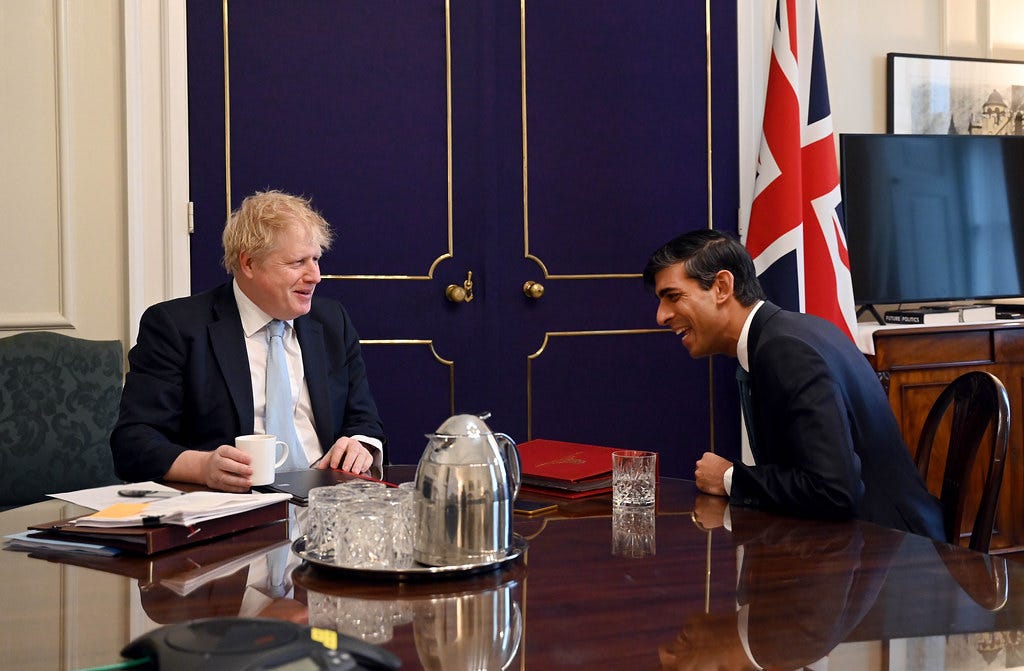

Is Boris still down to level up? Ask Rishi

In the process of surviving a confidence vote, Boris Johnson appears to have surrendered full control of economic policy to the Chancellor

On the eve of his victory in this week’s no confidence vote, Boris Johnson sent a briefing note to all Conservative MPs, reminding them of his many achievements in office.

Generously spaced and helpfully repetitive, the note just about filled a side of A4.

There was no room, however, for what might have been considered the defining mantra of the Johnson premiership (leaving aside Brexit), at least in terms of policy: ‘levelling up’.

Levelling up hitherto signified Johnson’s support for a more inclusive economic model, addressing persistent regional disparities. The agenda was distilled into a colossal white paper in early 2022, having been referenced 19 times in Johnson’s party conference speech in October 2021.

The government’s apparent commitment to addressing the North/South divide was central to its success in the so-called ‘Red Wall’. Many of the MPs who took seats from Labour in the North in 2019 have slender leads, and limited roots in their local communities – they will no doubt fear for their political futures if the levelling up agenda is aborted.

Achievements

Johnson’s achievements are listed in the briefing note as: winning a large majority; getting Brexit done; removing the pandemic-related public health restrictions (which his government introduced); supporting Ukraine following the Russian invasion; and the recent package of support related to the ‘cost of living’ crisis.

Levelling up seems a strange omission in this context, since the government can at least point to the introduction of ambitious targets, with some additional funding for local areas. None of this has yet borne fruit. But likewise, the success of most of the policies listed in the note is, at best, TBC.

In fairness, it is very early days, if the government’s objective is to turn around chronic inequalities many centuries in the making, tied to enduring political-economic structures which even the most dedicated government cannot ignore. But the note also refers – albeit in a single bullet point – to what a continuing Johnson government will do in the future:

“… by backing Boris Johnson, we can choose today to focus on growing the economy, cutting taxes, making our streets safer, and busting the NHS backlogs.”

There is rather a lot to unpack here, but the absence of levelling up is stark. In its place, there is a more general reference to ‘growing the economy’; while every government is of course bound to talk about growth the levelling up agenda is founded upon a critique of how the UK invariably tends to go after economic growth.

For example, in his own 2021 conference speech, Levelling Up Secretary, Michael Gove, argued that the 2016 referendum and 2019 election results were a verdict on a model of growth whereby prosperity is concentrated ‘in one part of our country’. And in the recent Queen’s Speech (delivered less than a month ago), economic growth is mentioned in the first sentence – but is quickly followed by a promise to ‘level up opportunity in all parts of the country’ in the third.

It is therefore revealing for economic growth to now be name-checked without caveats about ensuring growth is more evenly spread.

The second priority – cutting taxes – probably tells us quite a lot about why the first is presented as it is. Notwithstanding the fact that the Johnson government has raised taxes to historic levels, the clarion call of lower taxes demonstrates Rishi Sunak’s growing involvement in Operation Save Big Dog.

For completeness, it is worth noting that the three-page letter Johnson also sent to MPs in advance of the vote does reference levelling up. But only towards the end, after a dozen or so other policy priorities are mentioned. It is not referenced in the key passages on ‘driving growth’. The letter’s centrepiece is a joint agenda with ‘Rishi’ (referred to only with his first name) focused on deregulation and tax cuts.

The deal

Johnson is now very unpopular, with both the public and his own MPs. Arguably, Sunak’s lack of popularity is only among the former. If he can ride this out – allowing Johnson to absorb the bulk of the public’s animosity – then he remains the only serious candidate, among the current cabinet, to succeed Johnson as leader.

I would not be at all surprised if the outlines of a Granita-style understanding (or misunderstanding) already exist between Johnson and Sunak. Johnson might perhaps have suggested he will step down before the next election; Sunak is happy to be patient, with a decision on who will actually lead the Conservatives into the election dependent upon what the polls are looking like nearer the time.

(We should not be in any doubt that Sunak harbours an ambition to become Prime Minister. Why else would he continue to live in a country he clearly does not want to live in, and his wife agree to pay taxes she clearly does not want to pay?)

So far, so Granita. But what does this tell us about levelling up?

Sunak doesn’t like it, and the Treasury doesn’t like it. Sunak wants to cut taxes, or at least promise to cut taxes. The redistributive undertones of the levelling up narrative are therefore dangerous: the term did not appear a single time in his own conference speech last year.

The Treasury is not as ideologically committed to lower taxes as is often assumed, but it certainly dislikes anything with the whiff of muscular industrial or regional policy, as levelling up implies. The abstraction of ‘growing the economy’ is safer (i.e. less expensive) terrain.

So, Sunak takes full control of domestic economic policy, ending the incursion of Michael Gove. As a result, the discarded levelling up agenda will learn what it is like to be fathered by Boris Johnson.