Is it time to let the pension investment pipe dream die? (Part 1 of 2)

The constant demand that UK pension funds reorient their investment strategies towards patient and domestic growth assets ignores the structural constraints that face pension funds

Pension funds should invest more in the UK economy. That’s the view of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. It is always the view of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, whoever holds the role: even Kwasi Kwarteng managed to find time, in his 38-day tenure, to announce measures that would, apparently, enable pension funds to invest more in the UK economy.

While we await more detail about how Jeremy Hunt intends to pull the rabbit out of the hat, it is worth reflecting on the barriers to UK pension funds taking on riskier and long-term investments: this is the focus of part 1 of this post. Part 2 will explore the things that government could be doing do to make the magic happen – while noting there is little sign they are serious about reform in this area.

A little patience

Amid policy-makers’ near-constant proselytising, the reasons UK pension funds struggle to invest ‘patiently’ in the UK economy have rarely been properly acknowledged. There are four key issues worth noting here. Firstly, the legal (and arguably moral) imperative to prioritise – essentially to the exclusion of all else – the financial interests of members of the pension scheme limits the potential for these funds to play a broader social role.

There is scope for fund trustees to interpret members’ interests relatively broadly, but nevertheless regulation has in recent decades strongly reinforced the need to make investment decisions based solely on protecting these interests. Patient investments often involve risks that trustees deem incompatible with their legal obligations.

Secondly, the focus of attention for pension funds as patient investors has invariably been upon collectivist ‘defined benefit’ schemes, where outcomes for members are determined in advance of their capital being pooled for investment. The fact that employers guarantee these outcomes allows for a higher risk appetite and a focus on long-term returns. This model, however, has all but disappeared from the UK private sector, in terms of schemes open to new members and accruals.

In the individualised ‘defined contribution’ schemes which now dominate, due in large part to their role in the ‘automatic enrolment’ of most private sector workers into pensions saving, members’ outcomes are tied to the value of their pension ‘pot’ at the point of retirement, as determined by investment returns. This breeds fragmentation and conservatism in investment strategies (and this has been reinforced by the coalition government’s disastrous 2014 decision to allow early access to defined contribution schemes without a tax penalty).

We can point, thirdly, to the ideational dimension of financialisation. Risk management practices which are highly contestable are adopted without critical interrogation. Of course, protecting individual schemes and sponsoring employers from long-term uncertainty (a process reaching its logical conclusion in the rollout of defined contribution provision) has created myriad systemic risks. It hardly needs pointing out that a government led by Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt is highly unlikely to challenge this paradigm.

Structural inertia

The fourth set of reasons were outlined in an outstanding paper by Bruno Bonizzi, Jennifer Churchill and Annina Kaltenbrunner in New Political Economy recently. For Bonizzi et al, it is essential that we recognise pension funds’ liquidity needs, and their location within and dependence upon the UK’s increasingly market-based finance system.

In short, pension funds need liquid assets that can be quickly converted to cash. They are understandably allergic to risking value loss, but at the same time need return-seeking assets to match their liabilities.

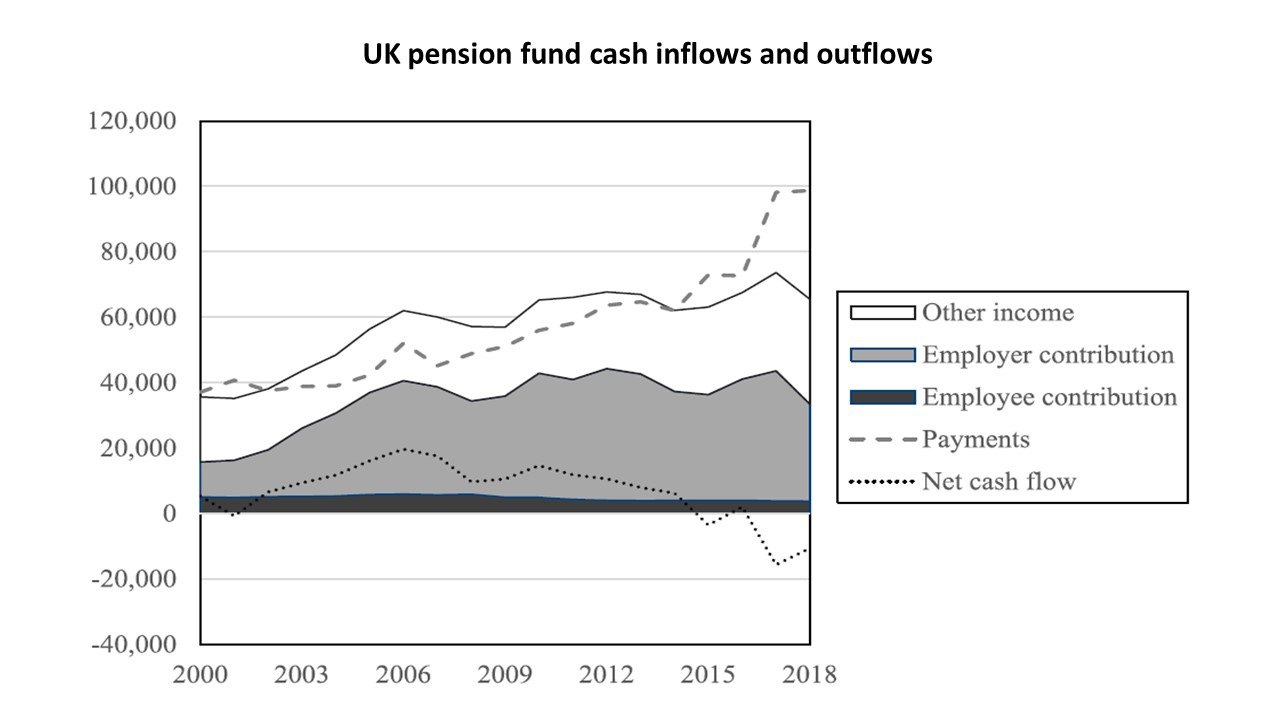

The need for cash arises partly from the obligation to make payments to retired members – with no (or very little) cash coming in from new contributions. Bonizzi et al’s key insight, however, is that demand for short-term liquid assets arises to a large extent from funds’ ‘need to engage in active liquidity management practices in the UK’s increasingly market-based system, characterised by the rise of collateralised financial relations’. Patient intent is therefore trumped by an impatience imperative. As the UK financial system has become increasingly ‘collateralised’ – assets derived from other assets need to be backed by something when traded – pension funds have been required to engage in evermore careful liquidity management. Yet they have simultaneously introduced more unpredictability around cashflow, since pension funds have little influence over the conditions in which calls upon collateral are made.

Bonizzi et al draw upon Daniela Gabor’s research to demonstrate that good-quality collateral is required to gain entry into pooled funds which seek returns as well as offering daily liquidity (through redemption of capital invested). Collateral is essentially being repriced on a daily basis; a far cry from the decades-long investment horizons we expect pension funds to maintain.

Clearly, things are difficult enough, in normal times. But financial volatility forces pension funds to occasionally dispose of assets rapidly, reinforcing conservatism in their investment strategies, while contributing to the pro-cyclical bias of financial markets – meaning volatile conditions arise more frequently.

This was apparent most obviously when bond markets’ reaction to the Truss government’s mini-budget in autumn 2022 undermined pension funds’ core collateralisation strategies (branded as ‘liability-driven investment’). Funds were faced with margin calls (demands upon their collateral) that they could not meet, in part because all funds were trying to do the same thing at the same time. The real risk, of course, was not to the solvency of pension funds, but rather to the banks which acted as counter-parties to the derivative contracts funds were relying upon. The result of Kwarteng’s budget was ultimately an even more constrained investment environment for pension funds (essentially under orders from the Bank of England to protect systemically significant private banks); i.e. the opposite to what he had intended.

The DC universe

The Truss-induced crisis mainly involved defined benefit schemes. Can we hope that increasingly dominant defined contribution schemes will avoid similar catastrophes, and indeed have scope to invest more patiently? Not really. Defined contribution schemes are taking in cash from working-age members. But, firstly, employer and employee contributions remain low (both in general, and due to too many legal loopholes). And in any case, defined contribution is individualised provision, so working-age member contributions do not fund payments to retired members (schemes are only for accumulation: they do not have retired members!).

Secondly, as Bonizzi et al identify, ‘defined contribution pensions, by design, allow investment flexibility to individuals and no liquidity support from employers beyond contribution levels, and therefore pay even closer attention to the daily management of liquidity’. They continue:

“Liquidity and daily pricing are paramount for defined contribution pension funds to ensure that their ‘liabilities’ are constantly marked-to-market in line with the market value of assets, and quick and ‘low-cost’ changes in asset allocation can be – in principle – made by individual pension savers. This suggests that, while the impact of defined contribution pension funds in terms of total pension assets in the UK is still limited, their rise might further boost the need for liquidity management practices and short-term nature of PF in the UK. This trend is therefore set to continue, as UK pension policy has moved to boost and entrench individualised defined contribution pensions, and with that the inherent constraints in their investment strategies.”

The inverted commas around ‘liabilities’ in the quoted passage above indicates the core defined contribution dilemma: schemes have no obligation to pay out actual pensions, but are required to make the full value of an individual member’s ‘pot’ transferable, well in advance of their retirement date.

We should also note that both defined benefit and defined contribution schemes are now highly dependent on a small number of asset managers to operationalise their investment strategies. This has led to greater uniformity in strategies, and a focus on scalable investment products such as index-tracking funds. Again, this is partly a result of the characteristics of UK pension funds (i.e. requiring liquidity), but also of a (concentrated) market structure that pension funds are forced to confront, but have little control over.

What we are asking defined benefit pension funds, and defined contribution providers such as insurance companies, to do is to disavow regular (and regulated) financial market practice, whilst entirely reliant on investment returns (defined benefit), or obliged to maximise the pot value of individual scheme members (defined contribution). As I argue in my book Pensions Imperilled, this is essentially impossible without employers or the state playing an anchoring role within the accumulation process – but the necessity and legitimacy of this function has been almost entirely eroded.

If all of this sounds extraordinarily complex, that’s because it is… and I have barely scratched the surface! My point here is that the characteristics of, and constraints upon, pension fund investment practice are rarely fully acknowledged by those who demand more patient and domestic-oriented investment strategies. In part 2 of this post, I will explore some of the latest proposals aimed at finally unlocking the potential of pension fund investments in the UK. Spoiler alert: we still have a long way to go.