It is time to admit that closing defined benefit pension funds was an epic mistake

Liability-driven investment is a product of zombie dynamics in UK pensions provision. But the present chaos was avoidable

Higher interest rates are supposed to be good for pension funds, right? Without getting too technical – well, not just yet – future liabilities are discounted with reference to interest rates, with higher rates allowing for steeper discounting, thereby closing or eliminating the gap between the value of a fund’s assets and liabilities.

If only it were that simple! The thing is, the UK does not really have many conventional pension funds anymore. We have zombie funds: the chart below shows the dramatic rise in the number of defined benefit schemes closed to new accruals. Only 11% of private sector pension funds are now open to new members and accruals, down from 43% fifteen years ago.

Zombie funds are not quite dead, but not alive either. They have assets, but no income from contributions. The consequence has been a large swing to ‘liability-driven investment’ (LDI). In 2019, the Investment Association (trade body for the asset management industry) estimated that half (£1.2 trillion) of the defined benefit pension assets under management by third-party asset managers were part of an LDI strategy.

LDI essentially refers to the practice of purchasing financial assets which match the profile of a fund’s short- and long-term cash requirements, with hedging strategies to guard against changes in inflation and interest rates (which would affect the value of liabilities). It’s a kind of financialised magic, you might say, squeezing cash from assets when there is no money coming in and more lucrative illiquid investments are impossible.

In this context, higher interest rates – or specifically, higher yields on gilts (government bonds) – have the opposite impact on pension funds’ financial health to what we would conventionally expect. But we misunderstand the present crisis if we assume that defined benefit pension funds are the principal victims of the interplay of LDI and higher interest rates. Funds which become irretrievably insolvent – a risk which has probably been overstated – would in any case fall into the Pension Protection Fund, covering a large portion of the benefits members would have received from solvent funds.

The issue in fact is the way in which LDI strategies interact with the rest of the financial system. But these potentially dangerous interactions have only arisen because of the unnecessary closure of defined benefit schemes. Rather than jeopardising the economy, collectivist pension funds could instead be supporting the UK’s economic development through long-term, patient investment.

Gilty pleasure

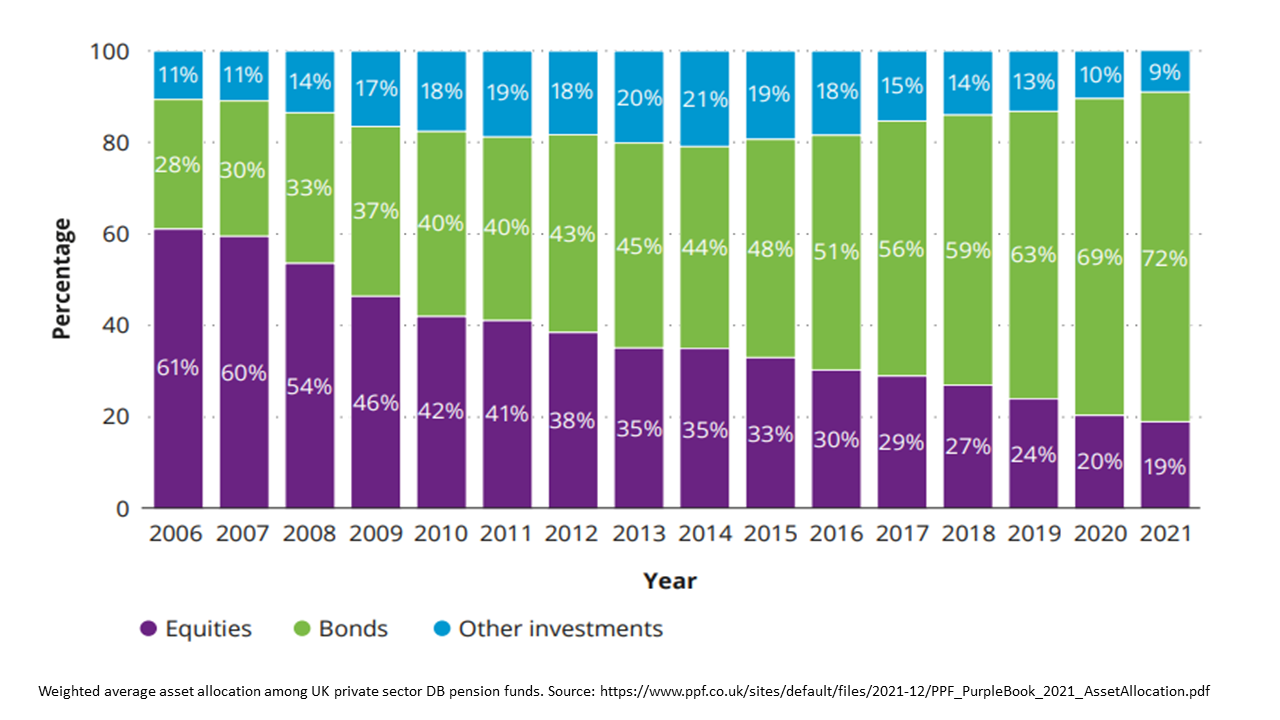

LDI has driven a seismic shift towards the relative safety of gilt investments among UK pension funds (see the chart below) – but this illusion of safety has proven to be highly problematic for funds using LDI in recent weeks.

More gilts means greater exposure to interest rates. This in turn means derivatives such as interest rate swaps are central to LDI too, to smooth cashflow (and perhaps produce marginal financial gains). Frances Coppola explains this far better than I can. I would also recommend Henry Tapper’s analysis; Tapper clarifies that pooled LDI funds are the main ‘poison pill’ we need to worry about. Many zombie funds are small, almost by definition, so their assets are pooled to enable an effective LDI strategy.

If you’re using swaps, then you need collateral. For pension funds, this means long-dated gilts, which, as luck would have it, they possess a ton of. But with yields rising sharply on newly issued gilts, long-dated gilts lose value due to lower secondary market demand. Collateral collapses, and the smaller funds cannot meet their margin calls.

So, why exactly did the Bank of England intervene? As tempting as it is to believe that the UK’s central bank is concerned above all about our pension funds, the truth lies on the other side of the swap contracts: the banking sector. As Coppola concludes:

[T]his is not a story about pension funds, it’s about banks. The gilt market freeze was creating a cash collateral shortfall for pension funds, and as a result banks were at risk of serious losses on derivatives. We’ve seen this movie before and we know it ends with large quantities of blood on the floor. That’s what the Bank of England feared. It intervened to stop the bleeding before it became a haemorrhage… When you dig deeply enough into a financial crisis, you almost always find it's really about banks.

Even if most UK pension funds were to suffer significant losses over a short period of time, this would itself be unlikely to cause a financial crisis (they did, after all, basically collapse 20 years ago). Ironically, as I report in Pensions Imperilled, pension funds had already started to move away from derivatives. But bank balance sheets are as fragile as they are structurally indispensable. The Bank of England announced therefore that it would become the buyer of last resort in the market for long-dated gilts typically held by zombie pension funds, mitigating the risk of contagion to the banking sector.

The Bank’s Governor, Andrew Bailey, caused panic on Tuesday evening by announcing that this programme would end on Friday (as originally intended). The comms were crap, but the decision itself should have been expected. One of the curiosities of the Bank’s intervention is that it has not actually bought very many gilts so far, since it has not wanted to pay much more than the current (depressed) market rate. It is clear that the Bank was mainly buying time for the banks, rather than bailing out pension funds. Bailey’s instruction to ‘get this done’ is telling pension funds to find cash quickly, ultimately liquidating assets and changing their investment strategies, for the sake of the greater good. (Financial Times reported on Wednesday morning that Bailey has apparently signalled to the banks privately that the programme could be extended if absolutely necessary.)

The Bank of course wants to start selling gilts – i.e. ‘quantitative tightening’ (QT) – rather than committing to buying more indefinitely. By pushing up yields further, QT might actually help pension funds over the long run. But the real intent is to constrain government spending in order to dampen inflation. Pension funds are a relatively small part of a much larger game from the Bank of England’s perspective.

DB/DC

The rise of zombie funds is perfectly explicable, even forgivable. The sponsoring employers of the defined benefit pension schemes in question have become less profitable, associated with wider trends of deindustrialisation and high street decline, as well as corporate restructuring resulting from acquisition by overseas firms. Combined with accounting rules that essentially treat pension liabilities as corporate debt, LDI is a logical feature of the phasing out of defined benefit provision.

The blame lies mainly with policy inaction. Rather than considering how to salvage collectivist provision, with guaranteed outcomes for members, UK governments from Thatcher onwards have instead supported the rollout of individualised defined contribution provision – with investment risks borne by scheme members – in place of defined benefit.

It would perhaps not be unreasonable to see the present chaos as merely a morbid symptom of the transition. The LDI-related problems we are seeing now could not reoccur in defined contribution provision, since the absence of the guarantee means that schemes essentially have no liabilities.

However, this would represent an over-optimistic account of the future of defined contribution provision. Defined contribution provision is in an expansionary phase, as younger workers are automatically enrolled into new workplace schemes. But its main investment practices are ultimately going to be similar to defined benefit provision as schemes mature, and avoiding losses and minimising volatility become higher priorities.

(Interestingly, the possible emergence of ‘collective defined contribution’ (CDC) – where members share risks with each other, but not their employer – could intensify this dynamic. There are many unknowns, but if the purpose of CDC is to provide greater certainty to savers about the outcomes they are likely to see in retirement, providing predictability without a sponsoring employer might well require LDI-like strategies.)

The main difference between defined benefit and defined contribution in practice is that the latter can rely on ongoing contributions, and a degree of permanence. But this is not an inherent difference. If defined benefit provision had been able to rely on these conditions, as well as an employer covenant, it would be every bit as viable. And if just 1% of the effort that has gone into designing an inferior system of individualised provision had gone instead into refashioning defined benefit provision, UK pensions might now be in a very different place.

We know this because local government pension funds, which are very mature but still open to new members and accruals, are in a very different place. So is the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) - the UK’s largest private sector defined benefit fund - despite repeated attempts by its executives and sponsoring employers to manufacture a solvency crisis which fundamentally does not exist.

Breaking the silence

The prospect of saving defined benefit provision from its unnecessary fate has been taboo for too long. The Resolution Foundation’s recent Intergenerational Commission, for instance, detailed the problems of defined contribution provision compared to defined benefit, but recommended only tweaks to the former rather than a revival of the latter. Similarly, IPPR is running a major Future Welfare State programme which seems not to focus on private pensions; the myriad risks associated with defined contribution provision and auto-enrolment for young people are not mentioned at all in the programme’s flagship report on ‘new social risks’.

Worse, Labour’s 2017 election manifesto promised to ‘restore confidence in the workplace pension system’, but made no reference to the inherent risks of defined contribution provision. The 2019 manifesto promised ‘an independent Pensions’ Commission’, but with a remit only to advise on contribution levels, not benefit design.

This silence has to be challenged. There will be space for defined contribution provision in the future, but there must be space for defined benefit too. The guarantee encompassed by defined benefit aligns with what most people understand pensions to be, because they instinctively and rightly believe that workplace pensions are not an investment product, rather an element of their pay. Accumulated capital will of course still be invested – indeed in ways which genuinely support rather than distort the economy, since schemes will be able to rely upon ongoing contributions and institutional stability when crafting investment strategies.

This is not to suggest that defined benefit provision did not need to evolve in light of economic and demographic change. But it is absolutely necessary to understand that a pile of assets (i.e. long-dated gilts) becoming illiquid is not the same thing as a scheme becoming instantly insolvent. Present circumstances render LDI inappropriate – so then abandon LDI. The best way of doing this, in my view, is to remove the need for LDI, by resurrecting defined benefit provision.

Way back when, we needed to support the development of multi-employer provision, like USS (multi-employer schemes are now the norm in defined contribution), building larger funds with longer-term investment horizons, shifting the balance of power between worker-controlled funds and the asset management industry back in favour of the former. Starting this from where we are now is not ideal, but still a better scenario than the one we are currently facing.

The state could support a new generation of defined benefit schemes by underpinning guaranteed outcomes. As noted above, the state already offers such guarantees via the Pension Protection Fund, as well as investing many billions in defined benefit schemes via Pensions Tax Relief. If the state is going to be called upon to support private provision anyway, it might as well operate transparently, and used to engineer a more sustainable private sector business model.

And the public guarantee could of course be conditional, with funds expected to invest in, say, the decarbonisation of UK industries and their supply chains. Indeed, once permanence is established, pension funds may be better placed than the state to undertake the gigantic investments now required (i.e. without inducing higher borrowing costs), assuming the state is prepared to mark out the necessary path via public financing.

Your point about DC and DB is reasonable. You might note that there is a superior alternative to both. We could support the consumption expenses of the elderly the same way we support the consumption expenses of the young (and how we support the medical expenses of the elderly): through a combination of family responsibility and the tax system. (I wrote about that here: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pensions-policy-breakingviews-idUSKBN18R20A).

At a more pragmatic level, the logic that makes finance types think bonds are lower risk than equities is insane. Equities perform with the economy over time and are inflation-protected. Bonds are playthings of central banks. It is obtuse, after a decade of negative real interest rates (long as well as short terms), for DB plans to concentrate on bonds. Only in the narrowest possible sense are gilts more "liability driven" than tracker equity funds.