The political economy of the Oasis reunion and working-class nostalgia

Noel and Liam’s transformation from artisanal labour to rent-seeking capital is complete

I was eleven years old when Definitely Maybe was released. I hardly ever listen to their music these days – occasionally I’ll hear it at the supermarket – but Oasis were undoubtedly the band of my adolescence.

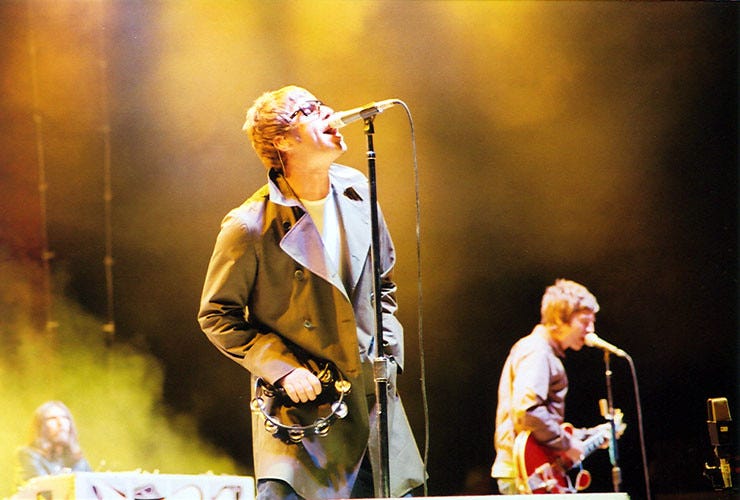

Their live shows were often underwhelming but the records were always better than – or something different to – what their critics remember. For me, however, there was always a significant identity element to my affection for Oasis. Proper Mancs, City fans, Irish lineage, brothers who liked a scrap. Their truths – no matter how messily articulated – were my truths.

I wanted their life, because it did not feel so different from the one I already had. Oasis made the teenage me feel like I could gain recognition for being good at something, without having to discard the version of myself I was born into.

Most of the discourse around Noel and Liam Gallagher’s decision to once again stand on the same stage to sing their hits has missed the mark. I am not really sure why anyone thinks the politics of a 90s guitar band need to be impeccably progressive, or indeed that the music played by a 90s guitar band needs to suddenly sound like something it never was.

In this post, I’ll offer something of a defence for their politics, and their art. What I won’t do, however, is celebrate the reunion itself. It’s not necessarily Noel and Liam’s fault, but the fact that Oasis announcing a tour has provoked such an intense media reaction – as well as extraordinary demand for tickets – is troubling.

Even in their heyday, the space for working-class cultural representation Oasis helped to expand soon contracted as the Gallaghers embraced celebrity and excess. The band (or brand) today occupies this space once again, but it is now one of little more than monetised nostalgia.

Working-class politics

The way the Gallaghers’ politics are discussed and understood mirrors the experience of many working-class people who dare to stray out of our lanes.

You can be a card-carrying communist revolutionary, true to your perceived class interests. But anything less left will see you labelled a bigot or, worse, a Brexiter – a useful idiot for the right’s eternal politics of divide and conquer.

This flies in the face of a reality in which working-class communities consistently demonstrate support for the centre-left. With little fanfare, working-class people drive progressive social and economic reforms, and always have. Of course, the deprivation many experience also serves as fertile ground for right-wing politics – Thatcherism for the lucky few who enrich themselves despite their disadvantage, and Faragism for those who misdirect their resentment – but these have only ever been minority pursuits.

As for the Gallaghers, Noel is a consistently inconsistent centrist, and Liam does not seem to have ever offered a serious opinion on any political issue, event or leader. As far as I’m aware, neither have offered the slightest degree of support for the Conservative Party, and certainly not the far right – quite the opposite in Noel’s case.

Welcome to Manchester

The Gallaghers do not even seem particularly patriotic, let alone xenophobic, despite the occasional use of the Union Flag in their merch. Noel in fact obliquely criticised an Anglo-centric worldview in one of his more thoughtful lyrics (the 2005 track ‘Mucky Fingers’). Noel and Liam’s love of football begins and ends with Man City; I don’t recall either being at all vocal about the English national team.

If the Gallaghers have a distinctive politics, it is essentially an anti-nobbishness, despite both being rather nobbish themselves. In other words, they are Mancunians.

The most alarming example of Liam’s immaturity is a fondness for homophobic insults. He did half-apologise for a homophobic slur aimed at Russian football fans in 2016, and told The Guardian in 2017 he wouldn’t ‘give a fuck’ if any of his children were gay. Strangely, the media seems largely uninterested in interrogating this documented aspect of Liam’s character, while happily insinuating a non-existent connection between Oasis and right-wing populism.

I wish they had used their good fortune to challenge injustice a bit more, but I’d say the same about almost every well-off person I have ever met. Most bands aren’t the Manic Street Preachers (I assume the Manics are quite happy about that).

Noel is good at writing songs, and Liam is good at singing them. It doesn’t qualify the Gallaghers to represent the working class politically – and it certainly doesn’t oblige them to do so.

Singing sad songs

One of the weirdest reactions to the reunion has been from the people insistent on explaining that, despite the millions desperate to spend a fortune on tickets, Oasis’s music isn’t actually any good.

Most of the time, everyone implicitly agrees that musical taste is subjective. Yet the people whose taste doesn’t extend to Oasis always seem so unsettled by the fact that anyone else likes them. Live and let mosh, I say.

As someone who once wrote an ill-advised ebook about Oasis B-sides, I don’t struggle to understand why so many still adore this band. They produced an extraordinary volume of very good tracks in the mid-90s – resulting in two classic albums, but it could and should have been four.

I pretty much gave up on Oasis after one listen of Be Here Now in 1997, although it took a while to wean. I last saw them live at Heaton Park in 2009 – for my stag night, no less – three months before the split. They already felt like a nostalgia act.

This does not mean there were not brilliant moments throughout their post-peak era. To reiterate: Noel is good at writing songs, and Liam is good at singing them. Artistically, they would both have been better off going solo much sooner: Oasis albums became an exercise in making sense of Noel and Liam’s different musical trajectories, and always ended up less than the sum of their parts.

The argument that Oasis are musically defective usually rests on two main falsehoods. First, they sound too much like the Beatles. This is a very silly argument. Oasis don’t have an original sound, but it is borrowed from an array of influences, and their early work sounds less like the Beatles than that of many more esteemed Britpop acts.

Second, they don’t have many fast songs: Oasis are the rock band that rarely rocks. This argument is not necessarily untrue, but it rests on a category error.

Oasis were successful because they specialised in mid-tempo plodders and Barlow-esque ballads, not despite this. Unlike almost all of their contemporaries, Oasis songs are often sentimental. Even the sillier songs, like first single ‘Supersonic’, capture something quite profound about loneliness and longing.

A remarkably high proportion of Oasis songs are basically about being in love. ‘Don’t Go Away’ – the song I heard at Morrison’s last week – is probably one of the most beautiful songs ever written about a son fretting over his mum’s mortality. Liam’s vocals are astonishing.

I think this emotional openness is a large part of the band’s enduring appeal, but it is something they are rarely given credit for. Of course, Noel’s (and especially Liam’s) lyrics are occasionally trite, and often nonsensical as they look to pad out a few lines of high school poetry to fill four minutes of radio. But they are usually heartfelt and sincere.

It works because it shouldn’t. Oasis are tough guys so it made it okay for other tough guys to express vulnerability – just not in a way that usually registers as artistic in a context in which working-class people in every cultural domain are pigeon-holed as authentically one-dimensional.

A different class

Above all, Oasis’s early albums are about escaping. The music matches the mood perfectly. You can argue that it’s all articulated quite inarticulately if you like, but it’d be daft not to acknowledge that this is part of why it appeals.

This is folk music, at its best and truest. Stood in a field with your arms around the lads who bullied you at school singing about Sally needing to wait is pretty much the same as singing about dead relatives in a County Mayo pub while your pissed uncle plays the fiddle (probably quite literally as big an influence on the Gallaghers as John and Paul).

The latter largely consists of music that is quite derivative and samey too, if we’re being honest. This doesn’t detract the tiniest bit from the warmth and meaning it encapsulates. When a rendition of ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ spontaneously broke out at a memorial for the Manchester Arena bombing victims in St Ann’s Square, the fact that nobody really knows what slipping inside the eye of your mind entails was irrelevant.

One of the things I find most frustrating about opinions on Oasis is when fellow proles criticise the Gallaghers’ working-class credentials.

Pulp are often held up as a comparison in this regard. Apparently, it is better to write wry stories about deprived childhoods in the 70s than it is to dream of breaking free from the conditions that made these childhoods deeply traumatising for some people.

I love Pulp – they are the only Britpop band I still regularly listen to. But I’d like to think Jarvis Cocker and co. would be among the first to recognise that it is absurd to argue that Oasis are somehow less working class because they pluck their strings differently. The argument was articulated most childishly recently by Welsh music journalist Simon Price (also a Manics superfan, by the way). Price has mistaken his right to think whatever he wants about Oasis’s music, for a right to diminish their lived experience of poverty. Accusing Noel and Liam of growing up in a big house in ‘leafy Burnage’ is perverse and, frankly, a really shitty thing to do.

And while we’re almost on the subject, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on how Oasis write about women. Liam might have lived a lads’ mag lifestyle in some ways, but the women in Oasis songs are usually depicted with respect, even awe.

I’m not sure I’d say the same about Pulp lyrics, although in fairness Cocker is often singing ‘in character’ as an oikish adolescent rather than expressing his own more considered emotions. And I definitely wouldn’t say the same about Arctic Monkeys (the band of my twenties), indie kids invariably seen as far more artistically credible than Oasis. Alex Turner’s lyrics are sometimes painfully misogynistic, depicting women (and girls) as little more than people that may or may not sleep with him. Even his love songs often rely on sexualised imagery to describe the object of his affection.

Let there be luvvies

All this said, is it a good thing that Oasis are reforming in 2025 for a lucrative reunion tour? Definitely maybe not.

My defence of Noel and Liam is essentially that, for a few short years in the mid-90s, they made a contribution to British culture that is more sizeable, and a lot more positive, than they have been credited with. Their critics are fighting bad-faith proxy wars about their musical quality and political impact that don’t stand up to much scrutiny or conform with common sense.

But the adverse reaction probably speaks implicitly to a more significant problem, related to what is happening now rather than what happened in 1995.

Oasis have evolved into a kind of national treasure. Always present, even though nobody really remembers why, like Harry Maguire or the Liberal Democrats. Except Oasis haven’t always been there: the fact that the brand hasn’t been used for fifteen years has helped to gloss over the mostly tedious years that followed their creative peak.

But such is the happiness that their return has seemingly inspired among many millions of people, the reunion is more like a monument to British culture than a contribution to it. The concerts should perhaps be treated as a public service, financed like the Last Night of the Proms – an equally mediocre but affirming musical experience.

I’m only half-joking. Nevertheless, we’re a long way from this situation. Working-class cultural institutions rarely get the full BBC treatment.

So the reunion is a commercial product, albeit one easily out-competing its rivals in the nostalgia marketplace. This means the only people who will get to enjoy it are the people who can afford to spend several hundred pounds on a night out, that is, precisely none of the people who currently live in the kind of circumstances Noel and Liam grew up with.

The crowds will of course be prole-adjacent: people with a working-class origin story who became better off at some point, working in IT or sales or becoming a member of the Parliamentary Labour Party.

All the while, today’s working class are increasingly under-represented in popular culture.

I don’t know if it could have worked out any differently. Being in a band is a very working-class thing to do, the modern equivalent to the artisanal labourers of early industrialisation. But to become a successful band, you have to turn your art into something else: a commodity.

And when the music is, fundamentally, based on vibes rather than sonic ingenuity, it can seem like Oasis are simply bottling up the trauma of the downtrodden in order to sell it back to them. It’s okay, I guess, because Noel and Liam felt and experienced it all first-hand – but it’s just, well, uncomfortable.

Like I said above, it’s not on Noel and Liam to take responsibility for the way the world is. But it’s on them, at least a little, not to exploit it.

But we’re all part of a masterplan, subject to forces we can never fully control. Oasis might once have been workers, but they have transformed into capital – a journey similar to the one everyone who buys a house goes on. Noel and Liam now resemble the pensioners in places like Bethnal Green, sitting on an asset worth many multiples of the value of the labour they put into it.

They were always going to liquidate at some point. It’s how the garden grows.

What a great article, funny and reflective.