Egalitarian social policy will make the economy more innovative

Evidence that more equal societies are more innovative shows that our understanding of what drives people to innovate is rudimentary

I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops. — Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda’s Thumb

If we want innovation, do we need to accept inequality? Our understanding of innovation remains wedded implicitly to the notion that most entrepreneurs are motivated by potential financial gains, and therefore that inequality is an essential background condition for innovation. The evidence suggests quite strongly, however, that more equal societies tend to be more innovative.

Thankfully, we have started to understand the role that the public sector plays in enabling and directing innovation processes, through public investment, anchoring innovation systems, embedding public purpose in innovation policy, and sustaining consumer demand. But equally important is the capacity and motivation to innovate at the individual level – the human roots from which any innovation process must emerge.

When innovation is considered through this lens, it starts to become clear that far too few people are being supported to develop the capabilities to innovate, have the resources necessary to innovate, and indeed are appropriately incentivised to take on the risks of innovating. This post, based on my recent paper, co-authored with Nick O’Donovan, ‘Entrepreneurial egalitarianism: how inequality and insecurity stifle innovation, and what we can do about it’, first considers why inequality may be impeding innovation. It then makes the case for progressive social policy in response.

The problem

Economic insecurity is at the heart of the story of how inequality impedes innovation. Innovation requires both deep learning and creative thinking, and there is mounting evidence that inequality inhibits these mental processes. Perceived threats to security give rise to stress responses that hamper memory formation and problem-solving, and children growing up in poorer households exhibit higher levels of stress hormones than their more economically secure peers.

This impact is not evident only in childhood. And nor is it exclusively a problem associated with low incomes or poverty. Greater inequality appears to correlate with larger numbers of stressors within society as a whole. Widening inequality can draw parts of the middle class into an increasingly precarious economic position, exhibiting hallmarks of insecurity such as high indebtedness or inability to meet unexpected additional costs. In addition, in more unequal societies, higher- and middle-income households have further to fall, and thus avoiding losses takes on greater significance than making gains – undermining individuals’ willingness to take risks.

In more unequal societies, fewer people have access to financial resources to invest in innovation: personal wealth plays an over-sized role in financing innovation. Social networks lubricated by wealth also help individuals to access private and institutional sources of innovation finance. These networks may also provide access to role models for would-be entrepreneurs. As communities become more stratified along lines of income and wealth – as has tended to be the case in many advanced democracies over recent decades – social networks become increasingly segregated, with access to the means of entrepreneurial aspiration increasingly distorted.

Inequality plays an important role in depressing demand for innovation. Low-income households struggle to diversify their consumption, meaning an increase in inequality decreases the market for new products. At the same time, increases in the disposable income of affluent households enable innovators to charge higher prices for high-end novelties, rather than productivity-enhancing innovations.

There is a geographical component to this story too: in unequal societies that exhibit geographical clusters of affluence and deprivation, would-be entrepreneurs based in economically marginalised communities and regions may struggle to access sufficient demand in their immediate environment to render new enterprises viable. Unequal societies also tend to be less trusting – organisational studies has highlighted the important contribution that trust makes to the innovation process.

The outlier

It is perhaps reasonable to conclude that the issue here is not necessarily inequality, but rather poverty and insecurity: we do not necessarily need to make the rich less rich in order to enhance poorer groups’ ability to innovate. However, to reiterate two of the arguments above:

High levels of inequality mean rich and poor increasingly live segregated lives, depriving the latter of access to the networks and markets that help to make innovation possible.

Inequality disincentives even more affluent groups from embracing the risks involved in innovation, because the consequences of not succeeding are severe.

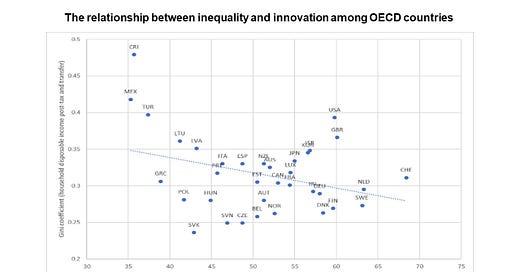

Accordingly, the chart below demonstrates well the link between equality and innovation at the country level, across 35 OECD countries. The inverse relationship between inequality and innovation is striking, and is consistent with broader macro-level evidence on the relationship between growth and equality. For example, a 2015 IMF study suggested that increases in the relative income share of the top 20% of earners tended to reduce the pace of medium-term growth.

The main outlier here is perhaps the United States, in being both very unequal, but among the OECD’s most innovative economies. It is surely, however, the exception that proves the rule that, despite common perceptions, the more equal countries of Northern Europe tend to be highly innovative.

It is possible, moreover, that innovation metrics tend to over-state the United States’ innovativeness. Patents, for instance, are a key component – but the relationship between patent registration and genuine innovation is now highly contested, with American tech firms using intellectual property rules to protect their market share against potentially innovate challengers.

We can also speculate that, as I argued in an earlier post, although the United States probably has a relatively low proportion of people who are able to innovate, it has enough people with sufficient income and other resources to produce an innovative economy. It does not however offer a replicable model.

The solution

If we want to support innovation – or specifically individuals’ capacity and willingness to innovate – the analysis here points us, perhaps counter-intuitively, to social policy.

The importance of social security systems is clear: for innovation’s sake, people must be spared the inhibiting impact of financial insecurity on learning and creativity. Even individuals higher up the income distribution must be convinced that, if they take career risks associated with innovation, experiencing a setback would not be catastrophic. Systems which provide meaningful income guarantees should be adopted – and they can become accessible not only when people fall into hardship, but also when taking opportunities to retrain, or starting a business or social enterprise.

Public services should be strengthened for similar reasons, with a ‘universal basic services’ (UBS) framework both socialising risks that tend to inhibit innovative activity, and encompassing a set of innovation services. This would widen access to the means of entrepreneurial aspiration, ranging from advice and networking opportunities to various forms of infrastructural support and access to finance.

It is vital that we cultivate more diverse lived environments, so that people from different backgrounds are better able to form social networks which may support innovation, and indeed so that the drivers of demand for innovation are more spatially dispersed. This has implications above all for educational systems, as well as housing and urban planning regimes – creeping segregation may be a larger part of the UK’s productivity problem than has yet been acknowledged.

‘Entrepreneurial egalitarianism’ makes a series of other recommendations, such as making public finance available to individuals at a much earlier stage of the innovation process, as a basic entitlement, perhaps through citizens’ wealth funds. We also explore the possibility of trade unions (with public funding) becoming spaces where workers from diverse sectors can experiment with and embrace novel career paths. It is important to build upon existing relationships of trust and co-operation, and trade unions (alongside similar and complementary organisations) could play a role in ‘backstopping’ some of the risks individuals take on when they embark on certain career choices.

Few believe that growth itself reduces inequality. A modified paradigm of ‘inclusive’ growth upholds that we can instead pursue economic strategies which produce more equitable outcomes. But what if this outcome – greater equality – is not simply an optional component of growth, but rather a pre-requisite of economic progress? The role that a more equal distribution of resources can play in supporting genuine innovation is difficult to dispute. If our analysis is correct, we should be looking beyond a narrowly conceived industrial and innovation policy domain, and considering also how social policy can make innovation happen.